I suppose, if you take a look at my works (ye mighty, and tremble), you might think that all I watch are bad movies. After all, I wrote for many years a site called The Bad Movie Report (hello, Web 1.0, if not.05). That part of my branding grew so ingrained that when I tried to write about something I thought was good, the e-mails would come in “How dare you even talk about [redacted] it’s not a bad movie!” Small wonder I eventually walked away. I’m claustrophobic; I don’t like being boxed in.

Just like everyone else, I enjoy a good movie. I just disagree at times about what constitutes a “good movie”.

This means there are holes in my education. Some -perhaps more than I would care to admit – are due to my pushing back against popular opinion. I don’t trust the masses. They can be kind of stupid. A lot more is due to availability. I can’t just turn on Netflix and watch Godard’s Breathless or Murnau’s The Last Laugh – I have to actively seek it out, find it, and probably pay for it, before I can even think of watching it.

So several years back, I started educating myself. I’m not getting any younger, and there are movies I heard about all my life, and have just never gotten around to seeing. I tried keeping lists of Movies I Will By God Be Watching This Year, and those didn’t really pan out. They’re still stuck on top of this page, if you want to see my failure. It’s just best for me to set aside a month and say, this month. The good stuff. I find Roger Ebert’s essays on The Great Movies a rock-solid starting place. Let us continue:

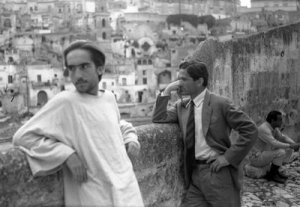

The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964)

I had been looking forward to this for some time, ever since experiencing Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Trilogy of Life movies (The Decameron, The Canterbury Tales, Arabian Nights). Having then experienced Pasolini’s controversial Salo, It seemed proper to finally indulge that desire. As Sean Frost pointed out, it’s not every director that has the guts to handle De Sade and the New Testament.

I had been looking forward to this for some time, ever since experiencing Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Trilogy of Life movies (The Decameron, The Canterbury Tales, Arabian Nights). Having then experienced Pasolini’s controversial Salo, It seemed proper to finally indulge that desire. As Sean Frost pointed out, it’s not every director that has the guts to handle De Sade and the New Testament.

Here’s the thing: I had been led to believe that this was a fairly politicized version of Jesus, and given Pasolini’s personal views, I really expected such. But there really isn’t that much of it in evidence here: there is a special emphasis on Jesus’ speeches to the masses between the triumphant procession of Palm Sunday and Passover, where he is really socking it to the Pharisees and generally sealing his eventual fate, and therefore, the redemption of Mankind. It seems a pretty traditional movie version of the accepted text.

But here’s the other thing: I’m not entirely sure I trust the print I saw.

The version that was available to me was on Amazon’s video service, and as a Prime member I had access to the movie for free. There are two things about that version that marred my experience: the first was a transparent watermark in the corner for Film Chest, which I was eventually almost able to ignore. The other thing, far more damaging, was that it was dubbed in English.

The version that was available to me was on Amazon’s video service, and as a Prime member I had access to the movie for free. There are two things about that version that marred my experience: the first was a transparent watermark in the corner for Film Chest, which I was eventually almost able to ignore. The other thing, far more damaging, was that it was dubbed in English.

Yes, I have been completely spoiled by the Criterion Collection.

My suspicious nature concludes that anything could have been substituted in the dubbing process. I also sort of doubt my own little paranoid conspiracy theory, but the dub job does the movie absolutely no favors. Flavorless, flat and rushed, it’s like listening to the English dub of Speed Racer, but without the charm.

There’s still a lot to like in the movie, however. Pasolini was able to do amazing things with a period piece on a limited budget, bits of Italy and Morocco standing in for the Holy Lands, embracing a low-level, unflashy aesthetic that adds significantly to the realism. He also has an eye for the most remarkable faces for the camera to dwell upon, sometimes grotesque, sometimes beautiful, always real and honest.

There’s still a lot to like in the movie, however. Pasolini was able to do amazing things with a period piece on a limited budget, bits of Italy and Morocco standing in for the Holy Lands, embracing a low-level, unflashy aesthetic that adds significantly to the realism. He also has an eye for the most remarkable faces for the camera to dwell upon, sometimes grotesque, sometimes beautiful, always real and honest.

I really did want my political Jesus, though. I wanted a movie version of Baigent, Lee and Lincoln’s The Messianic Legacy. Frustrated Gnostic that I am, I still feel Judas is getting a raw deal. But possibly Pasolini, lapsed Catholic though he was, still could not bring himself to totally smash some icons.

Buy Gospel According to St. Matthew at Amazon

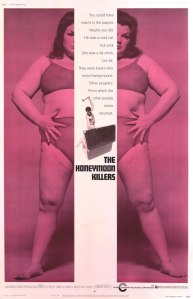

The Honeymoon Killers (1969)

You know what? It is suddenly a week since I wrote that last part. When I said I couldn’t possibly do a formal Movie Challenge, a movie a night for a month, I was being way more prophetic that I thought possible.

You know what? It is suddenly a week since I wrote that last part. When I said I couldn’t possibly do a formal Movie Challenge, a movie a night for a month, I was being way more prophetic that I thought possible.

The next flick I watched was The Honeymoon Killers, which is not on Ebert’s list, but it is in the Criterion Collection. It was my turn to pick a movie for the Daily Grindhouse podcast, and after two incredibly mediocre movies, we were ready for something better. It was a calculated risk on my part, because I’d never seen Honeymoon Killers, but I did know my first exposure to it was via one of Danny Peary’s Cult Movie books, so that seemed a fair indicator.

We were supposed to record last Wednesday, but Joe Cosby’s work had shifted into Hell Mode, so it was just going to be me and Jon Abrams. Then Jon’s workplace turned on him, and the podcast world doesn’t need an audio version of this blog. So it got delayed.

That is the shorthand version of last week. Crisis and exhaustion were the watchwords of the day, and when I managed to wind up in my easy chair, I didn’t have the energy for anything more involved than one of the many true crime shows on Netflix.

That is the shorthand version of last week. Crisis and exhaustion were the watchwords of the day, and when I managed to wind up in my easy chair, I didn’t have the energy for anything more involved than one of the many true crime shows on Netflix.

Speaking of true crime: The Honeymoon Killers is based on a true story – yeah, I know, we’ve heard that before – of a murder case from the late 40s to early 50s. TV show producer Warren Steibel and opera composer Leonard Kastle both hated the movie Bonnie & Clyde, feeling it was “too glamorous”, with even bloody violence given artistic merit. Steibel, wanting to branch out into movie production, managed to get $150,000 together – still peanuts, in 1969 – and convinced Kastle, the only writer he knew, to do the screenplay.

Kastle puts together a pretty good chronicle of the relationship between suave con man Ray Fernandez and overweight nurse Martha Beck, although all he had to go on was trial records and newspaper clippings. Kastle loved filmmakers like Goddard, Truffaut and Pasolini, and constructed the story like one of their neo-realist movies. The effect is a sort of documentary verisimilitude, a low-level reality, aided by the black-and-white photography (which also glosses over the fact that they could not afford to do a true period piece).

The center of the story is the unlikely romance between Ray and Martha, and how Martha’s jealousy interferes with Ray’s studied predatory gigolo procedures, and eventually leads to murder. That build-up leads to pretty horrific murder scenes that would be considered fairly tame these days, but have an added punch thanks to the relatively staid events leading up to them. Tony Lo Bianco and Shirley Stoler are perfectly cast, and carry the movie effortlessly.

The center of the story is the unlikely romance between Ray and Martha, and how Martha’s jealousy interferes with Ray’s studied predatory gigolo procedures, and eventually leads to murder. That build-up leads to pretty horrific murder scenes that would be considered fairly tame these days, but have an added punch thanks to the relatively staid events leading up to them. Tony Lo Bianco and Shirley Stoler are perfectly cast, and carry the movie effortlessly.

Kastle, who eventually took over direction after two others didn’t work out (and one was a young Martin Scorsese), may be taking his cues from European directors (and does a great job – his visual storytelling is efficient but elegant), but he also seems to derive some inspiration from the 1967 In Cold Blood, another piece of true-crime cinema with a black-and-white, documentary approach. Though in Kastle’s case, it was more a matter of financial necessity, which he then proceeded to exploit, and exploit very well. There are simply some things you can do with black-and-white that is impossible with color film.

Well, I had meant to save my babbling for the podcast, but I guess this is rehearsal, eh?

Buy The Honeymoon Killers at Amazon

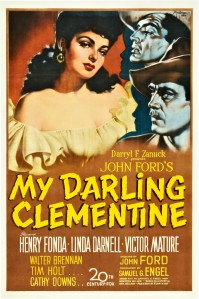

My Darling Clementine (1946)

One thing I learned about The Honeymoon Killers was just how much Kastle shortened and in a lot of cases, actually whitewashed the story: Martha Beck’s backstory was particularly heartbreaking, and the two were accused of over twenty murders, not just the four we witnessed. Well, Hollywood, and all that. The necessities of fiction, of telling a good story.

One thing I learned about The Honeymoon Killers was just how much Kastle shortened and in a lot of cases, actually whitewashed the story: Martha Beck’s backstory was particularly heartbreaking, and the two were accused of over twenty murders, not just the four we witnessed. Well, Hollywood, and all that. The necessities of fiction, of telling a good story.

Then how to address John Ford’s My Darling Clementine, the tale of the legendary Shootout at the OK Corral, where damned near nothing is true?

First of all, none of that is John Ford’s fault. The script is largely based on Stuart Lake’s posthumous biography of Wyatt Earp, Frontier Marshal, which in true Shootist style, is a collection of bunkum. The 1939 movie of the same name gets it just as wrong, if not wronger. To be sure, there is still a deal of controversy among historians about what exactly went down at the OK Corral, but we can be pretty sure that whatever it actually was, it wasn’t very photogenic.

In this particular alternate universe, Wyatt Earp (Henry Fonda) and his brothers are driving a herd of cattle west, and not doing a particularly good job of it. While the three oldest, Wyatt, Morgan (Ward Bond) and Virgil (Tom Holt) head into Tombstone to get a shave and a beer, the Clanton gang, led by Walter Brennan, rustle the cattle and kill the youngest Earp, James (a baby-faced Don Garner). The Earps take jobs as lawmen in Tombstone, at least until they can track down their brother’s murderers. Doc Holliday (Victor Mature) runs a saloon in town, and he and Wyatt strike up an uneasy friendship, strained all the more when Doc’s old girlfriend Clementine (Cathy Downs) finally tracks Doc down, and Wyatt takes a liking to her.

In this particular alternate universe, Wyatt Earp (Henry Fonda) and his brothers are driving a herd of cattle west, and not doing a particularly good job of it. While the three oldest, Wyatt, Morgan (Ward Bond) and Virgil (Tom Holt) head into Tombstone to get a shave and a beer, the Clanton gang, led by Walter Brennan, rustle the cattle and kill the youngest Earp, James (a baby-faced Don Garner). The Earps take jobs as lawmen in Tombstone, at least until they can track down their brother’s murderers. Doc Holliday (Victor Mature) runs a saloon in town, and he and Wyatt strike up an uneasy friendship, strained all the more when Doc’s old girlfriend Clementine (Cathy Downs) finally tracks Doc down, and Wyatt takes a liking to her.

Holliday, rather famously, is dying from consumption, and tries to send Clementine packing, egged on by his current girlfriend, a fiery saloon girl with the unlikely name of Chihuahua (Linda Darnell). Chihuahua’s fecklessness will eventually provide Wyatt with the piece of evidence he needs that the Clantons were responsible for James’ death, but that also gets her a bullet in the back from Billy Clanton (John Ireland). After that, it’s only a matter of time until everybody winds up at the OK Corral slinging lead.

This is Fonda and Ford’s first movie together after their tours of duty in World War II, and there is a tinge of melancholy and loss over the proceedings not evident in their pre-War work. Ford still works the atmosphere and period textures like few other directors ever managed, and some of the lighting effects in the nighttime scenes are spectacular – easily the best being the scene in which Holliday must operate on the wounded Chihuahua in the empty saloon, the improvised operating table illuminated by every oil lamp in the joint, surrounded by the deep black forms of people standing by, unable to help.

This is Fonda and Ford’s first movie together after their tours of duty in World War II, and there is a tinge of melancholy and loss over the proceedings not evident in their pre-War work. Ford still works the atmosphere and period textures like few other directors ever managed, and some of the lighting effects in the nighttime scenes are spectacular – easily the best being the scene in which Holliday must operate on the wounded Chihuahua in the empty saloon, the improvised operating table illuminated by every oil lamp in the joint, surrounded by the deep black forms of people standing by, unable to help.

That’s also a bit indicative of the post-War Ford spinning his wheels a bit, though; the scene is directly lifted from his earlier Stagecoach, right down to the drunken doctor calling upon nearly forgotten skills for emergency surgery, assisted by his patient’s hated rival. An earlier scene with Fonda delivering a monologue over James’ grave is also reminiscent of a similar scene in Young Mr. Lincoln.

You really sort of expect Tombstone to have been mysteriously relocated to Monument Valley – this is a John Ford Western, after all. The liberties taken with history only get more fanciful from there. Virgil was the Marshal in Tombstone, with Morgan, James and Wyatt occasionally pitching in to help. James, Virgil and, yes, Wyatt, were all married when they moved to boomtown Tombstone – dreadful sorry, Clementine. Holliday’s friendship with Wyatt went back several years before Tombstone, and unlike here and Frontier Marshal, he survived the Shootout. There were two Clantons present, and four other suspected rustlers, and only Billy Clanton and two brothers, the McLaurys, died.

You really sort of expect Tombstone to have been mysteriously relocated to Monument Valley – this is a John Ford Western, after all. The liberties taken with history only get more fanciful from there. Virgil was the Marshal in Tombstone, with Morgan, James and Wyatt occasionally pitching in to help. James, Virgil and, yes, Wyatt, were all married when they moved to boomtown Tombstone – dreadful sorry, Clementine. Holliday’s friendship with Wyatt went back several years before Tombstone, and unlike here and Frontier Marshal, he survived the Shootout. There were two Clantons present, and four other suspected rustlers, and only Billy Clanton and two brothers, the McLaurys, died.

Hell, these days we’re told the Shootout actually happened down the street from the OK Corral.

The lead-up to the Shootout is a great deal more complex than Clementine would have us believe, but the messy details of reality would only get in the way of a good story. It’s intriguing to consider that the version we’ve had on TV and in theaters for the past 65 years was trimmed of nearly 30 minutes by producer Darryl F. Zanuck, according to his own sensibilities and some preview audiences that necessitated retakes months after the movie wrapped. A nearly complete version of Ford’s version was actually discovered at UCLA in ’94. It’s not necessarily better, either, just… different.

Anyway, I think I now really need to watch something in color.