The Criterion 50% off sale at Barnes & Noble – the gift that keeps on giving.

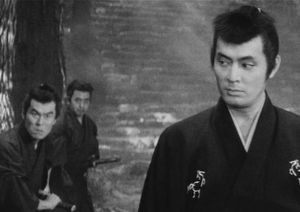

Criterion recently put out a Blu-Ray set of the well-regarded “Samurai Trilogy” by director Hiroshi Inagaki, a man with a prodigious filmography, and who pretty much defined the modern samurai movie. Taken from an incredibly popular serialized novel by Eiji Yoshikawa dubbed “The Gone With The Wind of Japan”, published several times here in the states under the simple title Musashi, (once in a five-volume paperback series, which gives you some ideas about the length and depth of the novel), it’s the tale of folk hero Miyamoto Musashi, a spectacular historical figure who was warrior, artist, and philosopher all-in-one.

Criterion recently put out a Blu-Ray set of the well-regarded “Samurai Trilogy” by director Hiroshi Inagaki, a man with a prodigious filmography, and who pretty much defined the modern samurai movie. Taken from an incredibly popular serialized novel by Eiji Yoshikawa dubbed “The Gone With The Wind of Japan”, published several times here in the states under the simple title Musashi, (once in a five-volume paperback series, which gives you some ideas about the length and depth of the novel), it’s the tale of folk hero Miyamoto Musashi, a spectacular historical figure who was warrior, artist, and philosopher all-in-one.

To say that Yoshikawa’s version of the man’s life is incredibly romanticized is not understating the case; though there are portions of Musashi’s life that are sketchy, we can be reasonably sure he was not the unpopular orphan presented in the first movie, Miyamoto Musashi. A wild, intense youth named Takezo (Toshiro Mifune, here looking very young, indeed) who runs away from his village to make his fortune in war, dragging his best friend with him. The best friend, Matahachi (Rentaro Mikuni) the best friend’s betrothed, Otsu (Kaoru Yachigusa), and numerous others who become entangled in his life over the next two movies, are all fictional. The Buddhist priest, Takuan (Kuroemon Onoe), who looks after Otsu, has some historic basis, but didn’t enter Musashi’s life until much later.

All of this isn’t too significant to enjoying the movie, which is, to be sure, a ripping yarn. Takezo and Matahachi are on the losing side of the Battle of Sekigahara, one of the great routs in Japanese history, and wind up taking refuge with two women, Oko and Akemi (Mitsuko Mito and Mariko Okada) mother and daughter who get by looting the bodies of dead samurai (which brings uncomfortable thoughts of Onibaba to mind). Both women fall for the wild Takezo, especially when he lays the smack down on a bunch of bandits, even when armed with only a wooden sword (Mifune and bandits – go figure). Oko’s lusty advances confuse the young man so much, however, that he runs away, and it is Matahachi who winds up escorting the women to civilization, eventually marrying Oko and forsaking Otsu.

All of this isn’t too significant to enjoying the movie, which is, to be sure, a ripping yarn. Takezo and Matahachi are on the losing side of the Battle of Sekigahara, one of the great routs in Japanese history, and wind up taking refuge with two women, Oko and Akemi (Mitsuko Mito and Mariko Okada) mother and daughter who get by looting the bodies of dead samurai (which brings uncomfortable thoughts of Onibaba to mind). Both women fall for the wild Takezo, especially when he lays the smack down on a bunch of bandits, even when armed with only a wooden sword (Mifune and bandits – go figure). Oko’s lusty advances confuse the young man so much, however, that he runs away, and it is Matahachi who winds up escorting the women to civilization, eventually marrying Oko and forsaking Otsu.

Takezo fights his way through a checkpoint to journey back to his village, and in doing so, becomes a fugitive – a contingent of troops moves into the village and a less than sympathetic samurai starts arresting villagers and forcing others to search the woods for the wild man. Intriguingly, none of these geniuses never stop to wonder just how the hell this guy is managing to take out trained soldiers with a wooden sword, but here we are. Takezo literally only wants to inform Matahachi’s mother and Otsu that his feckless friend is still alive, but after a betrayal by the mother, finds himself once again in the forest, now more a hunted savage than ever.

It’s the zen priest, Takuan and Otsu who eventually bring him in, and Takuan uses his long-standing friendship with the local lord to prevent Takezo’s execution. After a long, complicated series of escapes and captures, Takuan finally manages to trap Takezo in a room high in the lord’s castle, where he will spend the next three years, locked in a room full of books, sutras and manuals. He emerges a much more calm, worthier man. The lord proclaims he is now Miyamoto Musashi … Miyamoto for his home village, Musashi as an alternate reading of the ideogram for his name… and gives him a fresh start. Takuan advises him to make a clean break and not see Otsu, who has been living nearby all these years, but Musashi does anyway, and finds the meeting just as painful as Takuan predicted. Musashi leaves her once more to travel on a pilgrimage of training, leaving only the words “FORGIVE ME” carved into the railing of their meeting place.

It’s the zen priest, Takuan and Otsu who eventually bring him in, and Takuan uses his long-standing friendship with the local lord to prevent Takezo’s execution. After a long, complicated series of escapes and captures, Takuan finally manages to trap Takezo in a room high in the lord’s castle, where he will spend the next three years, locked in a room full of books, sutras and manuals. He emerges a much more calm, worthier man. The lord proclaims he is now Miyamoto Musashi … Miyamoto for his home village, Musashi as an alternate reading of the ideogram for his name… and gives him a fresh start. Takuan advises him to make a clean break and not see Otsu, who has been living nearby all these years, but Musashi does anyway, and finds the meeting just as painful as Takuan predicted. Musashi leaves her once more to travel on a pilgrimage of training, leaving only the words “FORGIVE ME” carved into the railing of their meeting place.

Miyamoto Musashi is a consistently beautiful movie, and one wonders if Inagaki’s willingness to remake his early 40s trilogy is due at least in part to the opportunity to film in Eastman Color. The film is shot totally on location, and the countryside and forest landscapes are amazing (and needless to say, eye-popping on Blu-Ray). The next two movies will rely more on studio sets and backlots, which rachet down the eye candy a bit, but has little real impact on the storytelling.

The second movie, Duel at Ichijoji Temple, finds Musashi well on his way to becoming the finest swordsman in Japan, never losing a duel. After defeating and killing an accomplished kusari-gama weilder, another priest admonishes him for being “too strong… entirely too strong!” This leads him into studying other disciplines, such as art, to temper his approach to life. An encounter with an unusually proficient and worldly sword polisher leads him into the world of music, where a courtesan running one of the better houses falls for him, once more to no avail. During this time, Musashi begins his famous series of duels with the Yoshioka fencing school, where the students, in order to protect their master, keep engineering ambushes to kill Musashi, usually to their sad disappointment.

The second movie, Duel at Ichijoji Temple, finds Musashi well on his way to becoming the finest swordsman in Japan, never losing a duel. After defeating and killing an accomplished kusari-gama weilder, another priest admonishes him for being “too strong… entirely too strong!” This leads him into studying other disciplines, such as art, to temper his approach to life. An encounter with an unusually proficient and worldly sword polisher leads him into the world of music, where a courtesan running one of the better houses falls for him, once more to no avail. During this time, Musashi begins his famous series of duels with the Yoshioka fencing school, where the students, in order to protect their master, keep engineering ambushes to kill Musashi, usually to their sad disappointment.

During one of these donnybrooks, enter Kojiro Sasaki (Koji Tsuruta), a swordsman of no small talent himself, who knows that he and Musashi will someday duel; he recognizes that the Yoshioka students are no match for Musashi, and moreover desires that Musashi gain more stature so that this future duel will have more meaning. Sasaki is another historical figure, and Tsuruta is fascinating to watch, a combination of feline grace and equally feline amorality. There are times he comes close to eclipsing Musashi as the star of his own trilogy.

Things come to a head at the titular duel, where Yoshioka’s disciples physically restrain him from going to the Temple so they can mount one last ambush against Musashi. Knowing he is walking into an ambush, Mushashi nonetheless takes on 60-odd Yoshioka men and manages victory, eventually meeting an apologetic Yoshioka, who he then defeats… but does not kill. A definitive step in the direction of his managing his sword, and not vice-versa.

Things come to a head at the titular duel, where Yoshioka’s disciples physically restrain him from going to the Temple so they can mount one last ambush against Musashi. Knowing he is walking into an ambush, Mushashi nonetheless takes on 60-odd Yoshioka men and manages victory, eventually meeting an apologetic Yoshioka, who he then defeats… but does not kill. A definitive step in the direction of his managing his sword, and not vice-versa.

Oh yes, Akemi and Otsu drop into the story every now and then to complicate things. At the end, Otsu is nursing Musashi back to health after the multiple wounds of the ambush, leading Musashi to remark that he has never felt such peace. Yielding to the moment, he does what every other woman in the series has begged him to do, and embraces Otsu, who shocked, fearfully repels him. Shocked and dismayed himself, Musashi leaves her once more, this time deciding it is probably best to avoid women. (Among Musashi’s many notable character traits, we can also count celibacy).

Duel at Ichijoji Temple advances the story very well, showing Musashi’s development as a man, even more than as a warrior, as he comes to realize that becoming a great man involves more than simple strength. As he explores the world beyond his sword, we begin to see the man who will eventually be revered as the great Sword Saint of his country.

If the movie relies more upon studio sets, it also has to be noted that Inagaki eschews Toho-Vision, a widescreen format that was becoming extremely popular, and continues to shoot in the older 4:3 format. This may seem to be limiting as far as image size goes, but the more traditional spherical lens allows him to milk as much depth of field as possible out of the color film, and this enables him to pull off some beautiful staging, especially in that climactic duel.

The final movie, Duel at Ganryu Island finds Musashi even further advanced down his path, no longer ardently seeking out duels, but filling out his experiences, taking up wood sculpture. Meantime, Sasaki still seeks his own fame, eventually rising to fencing instructor for a lord after crippling a retainer in a duel with a wooden sword (Sasaki visits the man afterwards, apologizing that he overdid it, which is the act that secures him the position). Sasaki and Musashi set their duel, which gets delayed for a year, while Musashi and two disciples head out into the boondocks for his next phase of development: he becomes a farmer.

The final movie, Duel at Ganryu Island finds Musashi even further advanced down his path, no longer ardently seeking out duels, but filling out his experiences, taking up wood sculpture. Meantime, Sasaki still seeks his own fame, eventually rising to fencing instructor for a lord after crippling a retainer in a duel with a wooden sword (Sasaki visits the man afterwards, apologizing that he overdid it, which is the act that secures him the position). Sasaki and Musashi set their duel, which gets delayed for a year, while Musashi and two disciples head out into the boondocks for his next phase of development: he becomes a farmer.

Of course, Akemi and Otsu are still looking for Musashi, and both run afoul of the bandits who are terrorizing the farmers, though Musashi and his two pals are terrorizing them right back (bandits again – go figure). It turns out that Akemi has connections with the bandits, and they send her into the village to tell the farmers that the bandits have been captured, so they can celebrate and be caught unawares when the bandits attack. Akemi tries to kill Otsu, accidentally triggering the signal for the bandits to attack; she then suffers a change of heart and dies protecting Otsu.

The bandits don’t fare too well in the fight, either. In the wake of the fight, a letter is delivered to Musashi, asking him to meet Sasaki at Ganryu Island, that they can finally have their duel.

Musashi prepares, returning to town, but staying with humble workers. Boatmen fall all over themselves volunteering to row him to the island. On the way, Musashi, as in the legend of his life, whittles a wooden sword out of an oar, to counter the length of Sasaki’s nodachi, the longsword. The duel is, appropriately, one of the visual highlights of the trilogy, fought on the beach, with the sun rising in the background. To no one’s surprise, Musashi wins, and looks down forlornly upon his fallen foe, telling the attending lord, “He was the finest swordsman I will ever meet,” before getting back in the boat to go home.

Musashi prepares, returning to town, but staying with humble workers. Boatmen fall all over themselves volunteering to row him to the island. On the way, Musashi, as in the legend of his life, whittles a wooden sword out of an oar, to counter the length of Sasaki’s nodachi, the longsword. The duel is, appropriately, one of the visual highlights of the trilogy, fought on the beach, with the sun rising in the background. To no one’s surprise, Musashi wins, and looks down forlornly upon his fallen foe, telling the attending lord, “He was the finest swordsman I will ever meet,” before getting back in the boat to go home.

The final scene is of the boatsman, ecstatic and happy that he is bringing back a living Musashi, while, at the boat’s bow, Musashi weeps bitterly.

Historically, he is twenty-nine years old.

Oh, yeah, Otsu showed up one last time to distract him. By this time you’re about ready to strangle her.

Duel at Ganryu Island is a solid trilogy closer. If it seems to lag in the first half, it certainly pays off in the second, with the bandit attack and that final duel with the awe-inspiring backdrop. We lost Matahachi and his comedy relief parents in the second movie, but wind up relying on Musashi’s disciples (reluctantly accepted by the swordsman) for lightness.

Duel at Ganryu Island is a solid trilogy closer. If it seems to lag in the first half, it certainly pays off in the second, with the bandit attack and that final duel with the awe-inspiring backdrop. We lost Matahachi and his comedy relief parents in the second movie, but wind up relying on Musashi’s disciples (reluctantly accepted by the swordsman) for lightness.

Considered overall, the movies are a remarkable achievement, made at a period when a Westernizing post-WWII Japan was just beginning to be released from the Allied occupation. It was a time when it became necessary to decide exactly what part of the country’s history would be carried forward into the new age, and what part should be allowed to be forgotten. Miyamoto Musashi, embodying a unique balance of warrior, poet, artist and philosopher, was a natural for continued reverence. I would love to see Inagaki’s other version of this trilogy, made in 1940-41, to see if they have a more nationalistic flavor, to reflect an empire at war.

Mention has to be made of Toshiro Mifune, though really, what more can be said? Mifune simply owns whatever movie he is in, and the casting here – the second time Inagaki had cast Mifune as Musashi – is perfect. He takes the role and his craft very seriously – compare how young he looks and seems in Miyamoto Musashi as opposed to Duel at Ganryu Island, though the movies were released a mere two years apart. 1954 was also the year Seven Samurai was released, so Mifune had a very good year.

Mention has to be made of Toshiro Mifune, though really, what more can be said? Mifune simply owns whatever movie he is in, and the casting here – the second time Inagaki had cast Mifune as Musashi – is perfect. He takes the role and his craft very seriously – compare how young he looks and seems in Miyamoto Musashi as opposed to Duel at Ganryu Island, though the movies were released a mere two years apart. 1954 was also the year Seven Samurai was released, so Mifune had a very good year.

Weighing in at less than two hours each, I almost watched all three in one night, that’s how drawn I was into the tightly woven story. That’s a commitment I would hesitate to suggest to non-chanbara fans, but for those of us who enjoy Samurai Cinema, this was time very well spent, indeed.

August 2, 2012

Categories: Movies That Do Not Suck . . Author: drfreex . Comments: 2 Comments

So, Stop Number One on my Netflix Instant queue: Resurrect Dead: The Mystery of the Toynbee Tiles. The basis for this is one of those pieces of true-life high weirdness I enjoy: there are a series of tiles embedded into roadways in the American Northeast that read: “Toynbee Idea/in movie 2001/resurrect dead/on Planet Jupiter” or variations thereof. There are often side panels that dangle tantalizing clues. These things have also cropped up in South America.

So, Stop Number One on my Netflix Instant queue: Resurrect Dead: The Mystery of the Toynbee Tiles. The basis for this is one of those pieces of true-life high weirdness I enjoy: there are a series of tiles embedded into roadways in the American Northeast that read: “Toynbee Idea/in movie 2001/resurrect dead/on Planet Jupiter” or variations thereof. There are often side panels that dangle tantalizing clues. These things have also cropped up in South America. This tale of amateur sleuthery is engaging, and it all seems to point in the direction of one individual, a virtual hermit in a Philadelphia neighborhood. All attempts to contact him are ignored, and eventually Duerr, convinced that he has shared a transit bus with the perpetrator, still decides to let the man walk away unbothered. “Let him go his way in peace, and let me go in mine,” says Duerr, who closes this chapter of his life and goes on to the next. The other two, we are told, are still investigating the phenomenon, especially the many copycats who have surfaced in recent years.

This tale of amateur sleuthery is engaging, and it all seems to point in the direction of one individual, a virtual hermit in a Philadelphia neighborhood. All attempts to contact him are ignored, and eventually Duerr, convinced that he has shared a transit bus with the perpetrator, still decides to let the man walk away unbothered. “Let him go his way in peace, and let me go in mine,” says Duerr, who closes this chapter of his life and goes on to the next. The other two, we are told, are still investigating the phenomenon, especially the many copycats who have surfaced in recent years. One of the conceits of Into Great Silence is that there is no narration, no commentary, no incidental music. Your experience is going to be just as silent as that of the monks. It is worth noting that this has the effect of making prayer and ecumenical chants that much more moving.

One of the conceits of Into Great Silence is that there is no narration, no commentary, no incidental music. Your experience is going to be just as silent as that of the monks. It is worth noting that this has the effect of making prayer and ecumenical chants that much more moving. Even after spending six months with the monks, Groning apparently still has the ability to experience boredom, as several times he chooses to switch to a lower resolution, and process a shot in a grainier fashion. I’m going to shrug at that. It’s not really necessary – but then, it could be argued that two hours and forty minutes isn’t truly necessary either. Although that slow build-up makes seeing normally silent monks shouting “Whee!” as they sled down a snowy slope all the sweeter.

Even after spending six months with the monks, Groning apparently still has the ability to experience boredom, as several times he chooses to switch to a lower resolution, and process a shot in a grainier fashion. I’m going to shrug at that. It’s not really necessary – but then, it could be argued that two hours and forty minutes isn’t truly necessary either. Although that slow build-up makes seeing normally silent monks shouting “Whee!” as they sled down a snowy slope all the sweeter.